Vintage Photography Accessories

Vintage Photography Accessories

Vintage Domestic Cameras

Vintage German Cameras

Vintage Japanese Cameras

Vintage Former Soviet Union Cameras

Vintage Polaroid Cameras

Vintage Prime Lens Comparison

Gallery of Images from Vintage Cameras

Vintage Viewfinder Attachments

Viewfinder attachments are often used on interchangeable lens cameras that do not have native viewfinder frames built into the camera's viewfinder to help with composing inages when using lenses that don't match the camera viewfinder. Generally, a camera's native viewfinder is designed to match a normal lens. Using a wide angle or telephoto lens requires a matching accessory viewfinder to accurate compose an image.

Shown a far left is an Argus accessory viewfinder for the Argus C3. As shown, a mask is in place for use with a Sandmar 100mm f/4.5 lens. When using the Sandmar 35mm lens, the mask is flipped up and back.

Near left is a Canon 135mm viewfinder attachment, a nicely constructed optical finder with a knurled ring distance adjustment around the eye port for accurate composition.

The attachments can be used on most cameras, regardless of make, with a matching lens. Parallax error is a big problem using these viewfinders, though, especialy if the accessory shoe is off center from the lens.

Vintage Rangefinder Attachments

Coupled rangefinders were rarely found on pre-WWII cameras except for a few top-tier brands. A few had built-in uncoupled rangefinders, but the setting had to be transferred to the camera lens, and then the image composed in a separate viewfinder. None of the Leica screw-mount cameras featured a coupled rangefinder, for example, despite their hefty price tages. Zeiss cameras, on the other hand, offered coupled rangefinders in the Contax, Contessa and Super Ikonta models, and perhaps other models as well.

By the mid-1950's, coupled rangefinders were fairly standard on non-SLR cameras. In fact, such classic cameras as the Leica M series, Nikon S series, and various pre-SLR Canon cameras became commonly called "rangefinder cameras" in the SLR era.

Three accessory rangefinders are shown here. Near left is a Kodak service rangefinder, along with its leather pouch and original box. The Kodak rangefinder mounts vertically, and is somewhat awkward to use. This one is very clean, with a bright image. When the image is brought into focus, the scale setting can be read from the knurled adjustng ring, and it can also be seen in the viewfinder, a nice feature.

At far left, bottom, is a German Akameter rangefinder that I purchased new in 1958 to use with my Agfa Silette camera. The scale is in feet. I still use it today on some of the old scale focusing folding cameras and other camera bodies lacking a built-in rangefnder. Although showing its age and use, it is still quite accurate, has a bright image, and is easy to use.

Also at far left, just above the Akameter, is a Russian Lomo "Blik" metric rangefinder attachment, along with its platic case. The vertical split image is a little more difficult to see than the Akameter's, but I purchased this rangefnder to use with a folding Voigtlander Bessa camera whose lens is marked in meters.

Vintage Light Meters

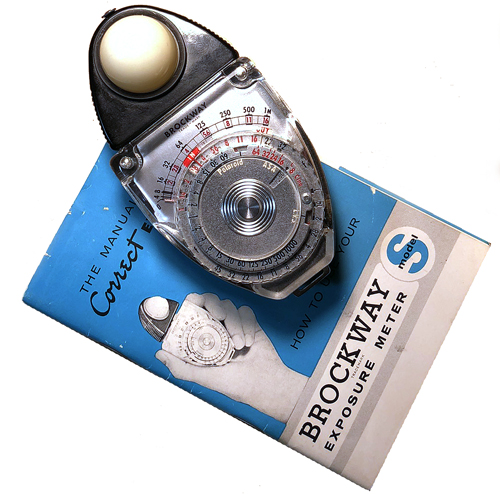

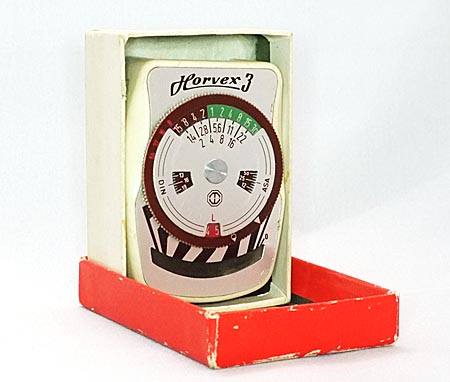

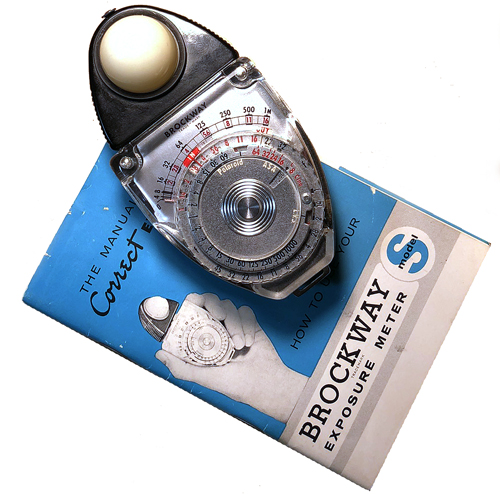

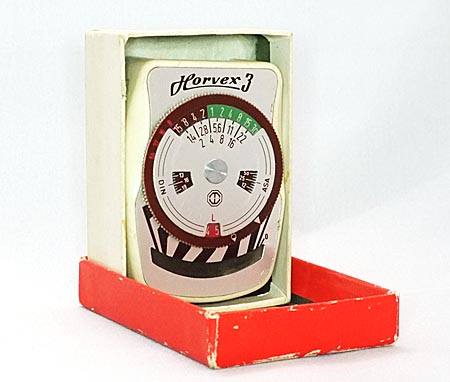

First image, left to right, a Weston Model 348, a Metraphot 3, and a Brockway Sekonic Studio Model S. Second image, a ca 1968 Horvex 3 meter in original box by Metrawatt. Before auto exposure, you either used your experience or the Sunny 16 rule to set exposure, or used the exposure guide printed on the inside of the film box, or a handheld meter, such as the four shown here.

The Weston 348 was Weston's only CdS meter and dates to the mid-1960's. Weston meters date to 1932, and were probably the first modern light meters available. All their meters are highly regarded, and would probably still be in use if batteries were available for them.

The Metraphot 3 used selenium cell technology, and could also be purchased calibrated for Leica shutter speeds. The Metraphot was tiny compared to other meters, such as the Westons or Brockways. The Metraphot was designed to mount on the camera's accessory shoe, but also came with a cover that slipped over the selenium cell so that the meter could be used for incident light readings. The Metraphot dates from the early 1950's. I used this one on my Agfa Silette.

The Brockway meter has an interesting history. It is strictly an incident meter using selenium cell technology. Brockway Camera was an inmport company that had imported Bolex movie cameras, and acquired the rights to the Norwood Director, a light meter developed by Donald Norwood and Karl Freund, a cinematographer. According to James Ollinger, Ollinger's Light Meter Collection, Freund filmed such classics as Metropolis and Dracula, and developed the three camera technique used for the I Love Lucy television show.

The Norwood Director was unique. It had a hemispherical dome over the selenium cell, which enabled to meter to average all the light falling upon the subject. The upper part of the meter over the dome could be rotated, allowing the photographer to stand to the side of the subject to avoid blocking the light. Brockway acquired the rights to the meter around 1955 and marketed it as the Brockway Director. At some point around 1960, the meter was sold or licensed to Sekonic, where it became the Brockway Sekonic Studio Model S. Sekonic soon dropped the Brockway name, and in the 1970's renamed it the Sekonic Model L-28A. The meter is still in production as the Sekonic Model L-398A.

The Norwood Director was unique. It had a hemispherical dome over the selenium cell, which enabled to meter to average all the light falling upon the subject. The upper part of the meter over the dome could be rotated, allowing the photographer to stand to the side of the subject to avoid blocking the light. Brockway acquired the rights to the meter around 1955 and marketed it as the Brockway Director. At some point around 1960, the meter was sold or licensed to Sekonic, where it became the Brockway Sekonic Studio Model S. Sekonic soon dropped the Brockway name, and in the 1970's renamed it the Sekonic Model L-28A. The meter is still in production as the Sekonic Model L-398A.

This one is still working and gives accurate readings.

Metrawatt appears to have made a variety of light meters during the post-war years in Germany, under various brand names, including some leading camera brand names. The Metrawatt 3, shown above, appeared as a house brand accessory clip-on meter for several cameras.

The Horvex 3, shown below, right, in its original box, was the third in a line of hand-held meters made by Metrawatt. The Horvex 3 was a 1960's era meter. This one belonged to my parents.

At left is a 1938 Weston Model 850 Junior hand-held meter that I found in an antique shop. I like the Art Deco styling. Light or sun rays, a common Art Deco design element, emanate from the silver screw bottom center.

At left is a 1938 Weston Model 850 Junior hand-held meter that I found in an antique shop. I like the Art Deco styling. Light or sun rays, a common Art Deco design element, emanate from the silver screw bottom center.

Rotating the thumb wheel at the top right of the meter changed the display in the window so the user could select the correct dial scale. James Ollinger, states that the Model 850 was Weston's first direct reading light meter.

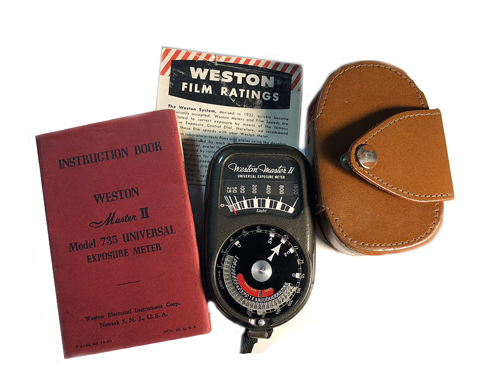

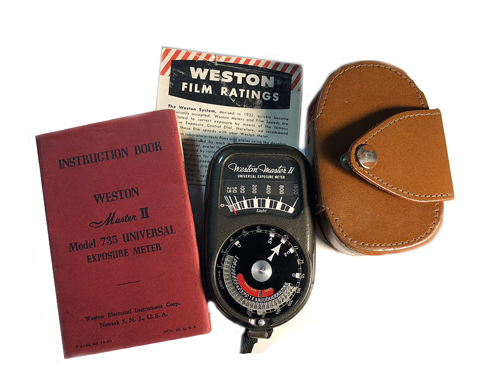

The development of the selenium photo cell lead to a number of new, accurate, and long lasting light meters, the Brockway described above being a classic example. At left is a Weston Master II Model 735 Universal Exposure Meter. Made from about 1945 to 1953, the Weston Master II became one of the most popular light meters carried by photographers during that era. Many are still working today and can be picked up for around $20 online. This example came with the instruction manual, a film speed ratings brochure, neck strap, and case.

The development of the selenium photo cell lead to a number of new, accurate, and long lasting light meters, the Brockway described above being a classic example. At left is a Weston Master II Model 735 Universal Exposure Meter. Made from about 1945 to 1953, the Weston Master II became one of the most popular light meters carried by photographers during that era. Many are still working today and can be picked up for around $20 online. This example came with the instruction manual, a film speed ratings brochure, neck strap, and case.

Using a grey card, I tested the one shown here against a Polaris digital meter and the readings matched exactly. The only problem with this meter is that the scales are so small that I have to use a magnifying glass to read the scales, rendering it useless for actual field use. It is, however, a prime example of American workmanship and manufacturing excellence during the mid-twentieth century. Build quality is excellent and the design is quite attractive. The meter is quite easy to use for an analog meter. Although ASA/ISO 100 was about the fastest speed film back in the early post-WWII years, ISO speeds up to 800 can be set on the meter.

Antique Contact Printer

I found this very beautifully made brass and wood contact printer in an antique store in La Mesa, California. I rewired it internally with period correct reproduction cloth covered wire, along with a new power cord and vintage style AC plug. The original momentary contact switch was broken beyond repair, so I had to replace it with a similar, but modern switch. It uses two light bulbs and has a built-in safe-light. The platen can accept negatives up to 5x7 inches.

Vintage Photography Accessories

Vintage Domestic Cameras

Vintage German Cameras

Vintage Japanese Cameras

Vintage Former Soviet Union Cameras

Vintage Polaroid Cameras

Vintage Prime Lens Comparison

Gallery of Images from Vintage Cameras

Home

The Norwood Director was unique. It had a hemispherical dome over the selenium cell, which enabled to meter to average all the light falling upon the subject. The upper part of the meter over the dome could be rotated, allowing the photographer to stand to the side of the subject to avoid blocking the light. Brockway acquired the rights to the meter around 1955 and marketed it as the Brockway Director. At some point around 1960, the meter was sold or licensed to Sekonic, where it became the Brockway Sekonic Studio Model S. Sekonic soon dropped the Brockway name, and in the 1970's renamed it the Sekonic Model L-28A. The meter is still in production as the Sekonic Model L-398A.

The Norwood Director was unique. It had a hemispherical dome over the selenium cell, which enabled to meter to average all the light falling upon the subject. The upper part of the meter over the dome could be rotated, allowing the photographer to stand to the side of the subject to avoid blocking the light. Brockway acquired the rights to the meter around 1955 and marketed it as the Brockway Director. At some point around 1960, the meter was sold or licensed to Sekonic, where it became the Brockway Sekonic Studio Model S. Sekonic soon dropped the Brockway name, and in the 1970's renamed it the Sekonic Model L-28A. The meter is still in production as the Sekonic Model L-398A.

At left is a 1938 Weston Model 850 Junior hand-held meter that I found in an antique shop. I like the Art Deco styling. Light or sun rays, a common Art Deco design element, emanate from the silver screw bottom center.

At left is a 1938 Weston Model 850 Junior hand-held meter that I found in an antique shop. I like the Art Deco styling. Light or sun rays, a common Art Deco design element, emanate from the silver screw bottom center. The development of the selenium photo cell lead to a number of new, accurate, and long lasting light meters, the Brockway described above being a classic example. At left is a Weston Master II Model 735 Universal Exposure Meter. Made from about 1945 to 1953, the Weston Master II became one of the most popular light meters carried by photographers during that era. Many are still working today and can be picked up for around $20 online. This example came with the instruction manual, a film speed ratings brochure, neck strap, and case.

The development of the selenium photo cell lead to a number of new, accurate, and long lasting light meters, the Brockway described above being a classic example. At left is a Weston Master II Model 735 Universal Exposure Meter. Made from about 1945 to 1953, the Weston Master II became one of the most popular light meters carried by photographers during that era. Many are still working today and can be picked up for around $20 online. This example came with the instruction manual, a film speed ratings brochure, neck strap, and case.